Lower US gasoline and diesel prices provides relief for consumer wallets; reinforces the benefit from developing US fuel resources, such as biogas.

We have all benefitted from the recent drop in gasoline and diesel prices (I know I have). US domestic oil and gas production are at the highest levels in history, which has led to reduction in costs for liquid petroleum fuels and natural gas. The reduction in fuel prices, we hope, spurs economic development in manufacturing and energy sectors, as well as providing some additional cash in the pockets of consumers, which should promote greater spending and confidence. We have seen broad-scale conversion of many aged coal plants to the use of natural gas turbines, taking advantage of both fuel economics and reduced emissions. But the question is ‘for how long?’ For sustained economic growth stemming from energy cost control, we must continue our efforts to develop our domestic energy resources. As a good friend of mine has said, “it is not time to start strategic planning when you are already in a crisis.” How can we plan for increased US energy independence in a bettering economy?

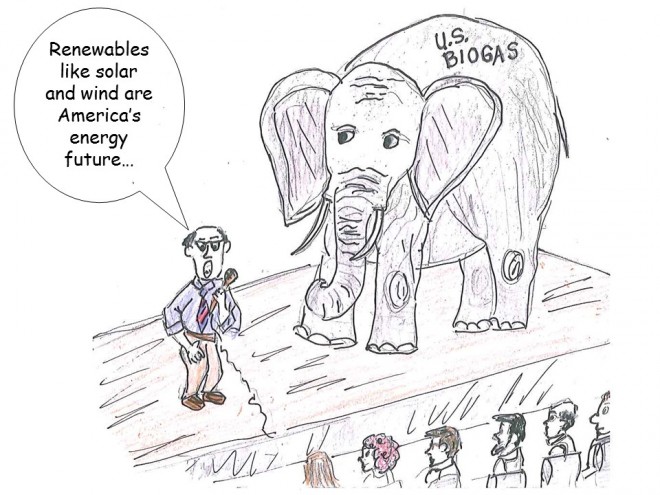

We frequently hear our elected leaders promote an ‘all of the above’ energy strategy; meaning, efforts to develop (economically) all forms of domestic energy, including both conventional fossil fuels and alternate forms of renewable energy. However, certain efforts have been gaining more traction than others; many times due to special tax incentives and policies that promote one approach over another. Federal tax credit programs and other federal incentives have aided in the proliferation of photovoltaic solar, which has resulted in the refinement of solar panel manufacturing costs. As construction contractors installed more and larger facilities, they identified ways to streamline installation costs, and experienced workers contributed even more to lowering the cost of these installations. Unfortunately, this level of investment in bettering the costs of renewable energy was mostly to the benefit of large-scale solar, as the environmental permitting, local zoning approvals, and other processes added to the time and expense of implementing other renewable energy technologies, such as biogas, wind turbines, and even new hydro.

Many states got on the bandwagon to aid solar development, too. Twenty-nine states have Renewable Energy Portfolio Standards (RPS), with few having specific set asides for certain types of renewable energy. While it is very encouraging that 29 of 50 states have an RPS, it is easily observed that the lion’s share of effort has been dedicated to the development of solar-electric projects, followed distantly by wind. Only one state, North Carolina, has made an overt attempt to promote bioenergy through its inclusion of set-asides for the development of renewable energy from swine waste and poultry waste, which it has had difficulty in realizing. Some of these states, such as my home state of North Carolina, added to the economic incentives through tax credits that were additive to those provided through the federal government. In NC, this meant that large-scale solar installations were eligible for 65% tax credits, and compared most other forms of renewable energy such as those described above, able to be installed with little ‘red tape’ resistance. Cost reductions, tax credits, and ease of siting paired nicely with the ‘easily-understood’ nature of solar farms, resulting in NC having more solar generation than almost all other states. It begs the question, though: should we have a more diversified approach, truly aspiring to an “all-of-the-above” strategy? Meanwhile, elected leaders contemplate the discontinuation of tax credits for the development of renewable energy systems, making it even more complicated, and less attractive to investors, to put their support behind non-solar renewables.

Some states, such as California, are taking an even more aggressive stance on promoting domestic energy markets. In his inaugural address in January 2015, California Governor Jerry Brown proposed raising the goals for renewable energy generation for Californians. The existing California goal is 33% of the electricity generation to come from renewable sources by 2020, and many Californians are confident that the actual generation will exceed this goal. Governor Brown’s proposal is to establish a new goal of 50% by the year 2030. In a move to further impact California’s carbon emissions and reliance on fossil fuels, the Governor is also calling for a reduction in fossil fuel use for transportation fuels by 50% and doubling building energy efficiency goals for existing buildings over this same time period.

The other states with renewable energy goals and requirements are struggling with ideas to promote a balanced, diversified approach to renewable energy generation. NGOs, advocacy groups, and even government agencies are gathering to discuss ways to provide support and guidance to state and federal policy makers on this issue. For example, in September of 2014, a group of renewable energy policy experts gathered at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC to share their experiences, data, and ideas with the states that have adopted renewable energy goals. At the time of this Summit, 29 states in the U.S. had adopted RPS, and 7 more have non-binding renewable energy goals. Representatives from 20 of these states were in attendance, as well as representatives of the US EPA, DOE, and various industry support groups such as the American Biogas Council and the Clean Energy States Alliance. Participants engaged in discussions regarding the continued promotion of well-informed renewable energy policy in the U.S., and for the states that may be revising their existing RPS, as well as those that may be on the pathway to developing a RPS of their own. Discussions were prompted by presentations from policy experts, including the US EPA on the impacts pending carbon emissions reduction regulations, referred to “111(d)” after the applicable portion of the Federal Register, have on RPS obligations.

And this is where the discussion gets complex, and often emotional. Many people express a strong belief in developing U.S. renewable energy, but the basis for these beliefs are often quite different. You have the “carbon emission reduction” camp, the “U.S. energy independence” camp, the “economic stimulus” camp, as well as many others. Unfortunately, though the common thread is pro-renewable, the means in which these camps wish to support its development are quite different. Thus, the debate continues on whether other forms of renewable energy generation, such as biogas systems, should be incentivized, mandated, or simply left to develop overtime without a stimulant.

Critics of bioenergy systems are quick to point to costs and competition with food-chain agriculture as reasons for lesser investment in developing bioenergy resources. However, when pressed for data to support these excuses, the conversation tails off. If we can use history as an indicator, it would seem that manufacturers and developers learned ways to drastically reduce the costs of solar, and to a lesser extent, wind through increased iteration; meaning, as more of these systems were built, the less capital intensive they became. This has been true for nearly all U.S. innovations, from the automobile to the solar panel. Why do we expect it to be any different for bioenergy systems? If we truly wish to see the cost of these systems reduced, we must find ways to support their evolution and improvement from one generation of system to the next.

The more emotional, if not emotion invoking, argument is the competition with food waste. Nay-sayers recount previous use of corn in the production of ethanol, and calling to question the diversion of edible materials to biofuel production. This is a very valid argument, and one that I happen to agree with. However, as any corn farmer will tell you, about half the corn plant lies on the surface of the field after harvest as corn stover (the inedible stalk, leaves, and cob). Naturally, a significant portion of this material decomposes in or on the topsoil, resulting in the release of methane and carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. According to the US EPA, agriculture contributes about 24% of the global carbon emissions, trailing power generation at approximately 30%. Perhaps an opportunity that satisfies all “camps” is to promote the harvest these stovers and residues to use as feedstock for bioenergy systems, such as anaerobic digestion, to create a biogas (natural gas alternative), methanol, and other energy fuels. Use of these materials and fuels recycles carbon that is already above the earth’s crust (that which we are trying to manage) lessening the need to pump ‘buried carbon’ to the surface, adding to the amount to be managed. In fact, many scientists and technologists are working to develop systems to sequester atmospheric carbon by injecting it through wells deep into the earth’s surface. Wouldn’t it make sense to simply slow how much we extract, replacing it with recycled carbon (bioenergy)?

Alternately, utility-scale solar is, in many areas, competing with food-chain crop production. In some places, such as near my home in eastern North Carolina, it has become more economically viable for farmers to convert some of their otherwise-arable lands to solar farms. Conversion to solar farms renders this land fallow for 10, 15, or even 20 years or more. Now, I am not ‘knocking’ solar at all – in fact, I am a fan of it. I also recognize that we must increase our food and fiber production in the coming years to satisfy a rapidly growing global population. I remain an avid supporter of developing a well-informed plan, or blueprint, to renewable energy development – which seems to be lacking right now for most states debating the future of renewable energy development.

Other considerations include variability of power generation. Antagonists have long pointed to the “solar doesn’t work at night” argument and the “turbines don’t spin when the wind don’t blow” arguments. To address these concerns, both the wind and solar industries have begun illustrating a partnership with the natural gas industry to include ‘peaking gas turbines’ to level the generative capacity when the variability of solar or wind are at their greatest. Why not bioenergy? Given the considerations discussed above, it would seem that bioenergy, and more specifically biogas, would be the perfect ‘peaking’ companion, as many bioenergy systems are benefitted by waste heat created through the combustion process. Regrettably, at a recent renewable energy-themed conference, I observed a representative of one of the 29 RPS states ask “what is biogas” – pointing to the great need for bioenergy supporters to conduct outreach and education of the public, regulatory officials, and elected leaders.

Regardless, of your basis for opinion on our U.S. energy policy, I think one thing is for sure – renewables have to be part of an “all-of-the-above” strategy, and will be part of our energy future in the U.S. Hopefully, we can work to identify the barriers, obstacles, and inhibitors to the development of all renewables – not just solar – and prepare roadmaps for the more logical, efficient development of our renewable energy resources. Most energy experts agree that a diversified approach is most healthy and beneficial, but U.S. renewables are grossly weighted to solar at present. We need more informed strategies – let’s grow our energy crops on lands not suited for food production, and harvest waste residues from the non-edible parts of the plants. Let’s repurpose animal manures to include bioenergy production in addition to nutrient recycling. Let’s farm food, not solar; and incorporate solar collectors in our built environment, atop roof systems, parking decks, and in areas not suited for food production. Let’s build wind turbines in the windy areas, and capitalize on hydropower at impoundments. Through development of such a balanced, if not smart, strategy, we can reap the benefits we so desire from renewable energy sources, rather than prompting our grandchildren to ask “what were they thinking”?